An introduction to pellets

2016-08-31

【Global advanced bio energy information August 31st】Pellet fuel is a renewable, clean-burning and cost stable home heating alternative of increasing importance throughout the world. It is a biomass product made of renewable substances—generally recycled wood waste. Millions in Europe and the United States use wood pellets for heat, in freestanding stoves, fireplace inserts, furnaces and boilers. Pellets are also used in industrial applications and to generate electricity as a substitute or complement to coal in cogeneration projects. Pellet fuel for heating can also be found in such large-scale environments as schools and prisons.

Cordwood, wood pellets, wood chips, waste paper, along with dozens of other agricultural products and by-products capable of being used for energy, are all examples of biomass fuel. The most compelling principle of biomass is that it is renewable. The remarkable consistency and burn efficiency of pellet fuel produces a fraction of the particulate emissions of raw biomass. Pellet burners feature the lowest particulate matter emissions of all solid fuels burners. Given the proper initiatives and agricultural management, biomass is virtually limitless, and has proven to be pricestable in comparison with fossil fuels.

The use of biomass pellets for energy dates back to the 1970s when alternatives to fossil fuels were sought in the wake of the energy crises of the decade. At this time, the technology used to produce animal feed pellets was modified to accommodate denser, woody materials. One of the industry’s early movers was Sweden due to its prominent timber industry, desire for increased energy independence and its commitment to environmental conservation.

Wood pellet production planning in Sweden started in the late 1970s with the decision to build a pellet plant in Mora. The plant started production in November 1982 and immediately ran into problems because costs were much higher than had been calculated. Equipment was developed for converting oil boilers to pellet-fired boilers. In practically all cases, however, they were highly inefficient, not least because of the poor pellet quality. During this first year the raw material was usually bark. Pellets often had an ash content of 2.5% to 17%. The plant in Mora was closed 1986.

In 1984 a pellet plant was built in Vårgårda. The plant’s last owner was the Volvo group. It was closed in 1989. In 1987 the first plant for pelletizing dried material was built in Kil. It was designed for an output of 3,000 metric tons a year. This plant is still in operation and is the oldest commercial plant in Sweden.

In the early 1990s the Swedish government came up with a proposal for taxation of mineral fuel. At this time it also limited carbon dioxide emissions. In a short time period the prospect of burning fossil fuels became unprofitable with biofuels stepping in to fill the energy void. This marked a turning point and the use of wood pellets started to grow rapidly.

Similarly ambitious clean energy programs emerged elsewhere in Europe. As a result, Europe leads the world in biomass pellet consumption to this day. The level of sophistication has risen on the continent to such an extent that manufactured pellets can be delivered in bulk via tanker trucks and deposited directly in residential storage areas, similar to the way gas stations are restocked with gasoline.

North America

The wood pellet fuel industry became established in the mid-1980s with the introduction of the residential wood pellet stove. This appliance was capable of reducing particulate emissions well below the new requirements of the U.S.’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for wood stoves and of providing consumers with a new level of automation and convenience for heating with wood. Sales of pellet stoves increased rapidly in the early 1990s, reaching a peak in 1994 before leveling off and declining somewhat due to competition with natural gas stoves.

In 1984 there were two pellet plants operating in the Pacific Northwest of the US. The majority of pellet plants are owned by small companies established specifically for that purpose. However, recently many large facilities have come online in response to rising demand in Europe, which has emerged as a key export destination for Canadian and American made pellets.

The raw material used is commonly sawdust. Shavings and chips are used to a lesser extent. The industry is a mix of stand-alone plants, whose only business is pellet production, and plants that are part of other wood-processing companies. The stand-alone firms buy their raw materials on the open market and tend to be larger producers. The add-on operations usually process only the residues generated by the company’s wood processing activities.

The wood pellet industry has a history of slow plant start-ups. Many plants have required six to eighteen months after starting to normalize operations. The long start-up periods were due to a variety of factors including: variations in raw materials, inadequate design and engineering, use of worn-out or improperly sized equipment and inexperience on the part of management and production workers. Nonetheless, conditions continue to improve as the industry matures, firms more extensively research the process before entering the business, improved equipment, better overall plant design and installation by equipment/engineering firms, and the information and assistance provided by other pellet producers.

In addition to large production facilities, individuals—particularly in rural areas have found it beneficial to produce their own pellets using small-scale machinery. These practical, often mobile pellet presses confer a certain level of energy self-reliance to the user as well as a means to derive economic benefit from readily available waste materials.

Why pellets?

Environmentally friendly

The main appeal of wood and biomass pellets is its carbon neutrality. Living plants take in carbon dioxide and expel oxygen. After the plant dies, this carbon dioxide is released naturally during decomposition or when the plant is burned as a source of biomass energy. Net gain in atmospheric carbon dioxide: zero. In contrast, burning fossil fuels releases carbon dioxide that would otherwise have remained stored, accelerating global warming. Furthermore, biomass energy utilizes materials that might have otherwise been discarded as waste.

Convenience

Why not burn logs, woodchips, or other raw forms of biomass? One reason is moisture content. Even in seasoned wood the moisture content tends to be around 30 percent; compare this with less than ten percent for wood pellets. The result: significantly less smoke from burning pellets. Second, pellets produce less ash since contaminants such as soil and bark, found in woodchips, are removed during pelletization. Third and most importantly is energy density, which is more than three times greater in wood pellets than in woodchips.

To recap the convenience of pellets:

Density of around 650 kilograms per cubic meter

Flows like a liquid; ideal for automatic systems

Can be used in stoves and boilers

Can be used in small and large scale applications

Easy to handle, store and transport

Improved combustion characteristics over raw material

Wide range of raw materials

Sawdust is the most common raw material used to make pellets, as it requires less pretreatment before entering the mill. Nonetheless, a variety of raw materials have been shown to make viable pellets. Options range from a diverse array of wood waste (residual sawdust, wood shavings and wood peelings, etc.), yard debris (grass, leaves, sticks, forsythia, wisteria and bushes), farm waste (corn cobs, corn stalks, and straw from plants) and other residual biomass waste.

Some of the most common species of agricultural biomass used to make pellets include: reed canary grass, miscanthus, switchgrass, cardoon, olive and rapeseed, sunflowers, grapes and citrus fruits.

Quality pellet characteristics

In the premium wood pellet market a “quality pellet” refers to a pellet with very low ash, for example, 0.3 percent. This book describes all types of biomass pellet production; some of the pellets produced will have higher ash content. A quality pellet is defined by its mechanical durability and moisture content.

Mechanical durability

Mechanical durability simply refers to how dense the pellet is, and how well it is formed. Pellets that are denser are of course stronger, and can better withstand the impact from transportation. They also function more efficiently in the pellet burner. When a quality pellet has exited the pellet mill, it should have a smooth surface, with little or no cracks. If the pellet is cracking and expanding it is because there is too much moisture within the pellet, or there was poor compression within the pellet mill.

Once a quality pellet has cooled, it should be like a coloring crayon. The surface of the pellet should be smooth and lustrous.

Wood pellets tend to shine more than others; the most important thing is the pellets smooth compact state. Try tapping the pellet against a hard surface to see if the pellet stays intact, or if it crumbles easily. The length of the pellet is not really that important. However if pellets are too long (above 1 inch) they can cause damage to the auger in the pellet burner.

Moisture content

The less moisture within a pellet, the more energy the pellet burner can use.

However, a certain percentage of moisture is required in the pelleting process, so the target is to keep moisture as low as possible while still creating quality pellets. The target should be to obtain a finished pellet moisture content below 10 percent.Pellets with more than 10 percent moisture will still burn, but at the cost of efficiency.

Ash content

Wood is overwhelmingly preferred to other widely available options, notably agricultural wastes. This is in part due to agricultural wastes' low density—which increases transportation and storage costs--its greater ash content, and to its high levels of undesirable elements such as silica, calcium, potassium, chlorine and sulfur.

These minerals are imparted in the crops by fertilization. When burned, agricultural materials such as straw tend to leave more slag—a sort of black crust—on the interior of the boiler and heat-transmission equipment. Chlorine corrodes the metal.

This is bad, but can be mitigated with specialized boilers, and by controlling the amount of fertilization and time of harvest.

Quality pellet test

As stated, quality pellets should have moisture content below 10 percent and be mechanically strong and dense. The simplest way to test pellet quality is to place a pellet in a glass of water, if the pellet sinks to the bottom the pellet has a high density, and was formed under sufficient pressure. However if the pellet floats it will be a poorer quality pellet with a lower density, lower mechanical durability and more likely to crumble and produce fines.

The second test is to take a vessel, which can hold at least 1 liter of water and weight it. Fill the container to the top with pellets and weigh again. Now fill the container with water and weigh. Deduct the weight of the container from both measurements, and then divide the weight of the pellets by the weight of the water.

For quality pellets the results should be between 0.6 and 0.7 kilograms per liter—a figure that may also be referred to as the pellets’ specific gravity. Specific gravity is a crucial indicator that the pellets were produced under the correct pressure. Poor quality pellets, for example with a specific gravity under 0.6, will break/crumble easily, and produces excessive fines.

Industry standards

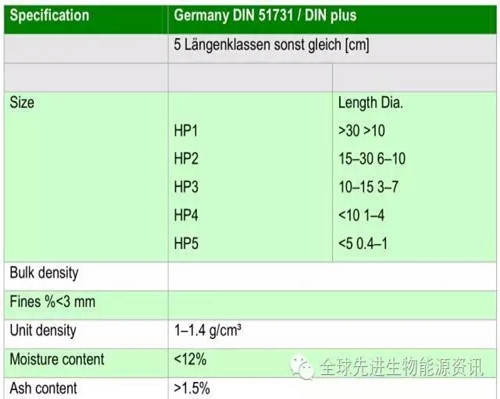

A number of countries have established their own standards; however in Europe there is an attempt to consolidate the regulatory environment for biomass pellets under the European Committee for Standardization.

American Standards

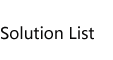

The solid fuel standards that exist in the United States are determined by the Pellet Fuel Institute (PFI). Compliance is voluntary. The table below lists the specifications for pellets across three classes: premium, standard and utility.

European Common Standard (CEN)

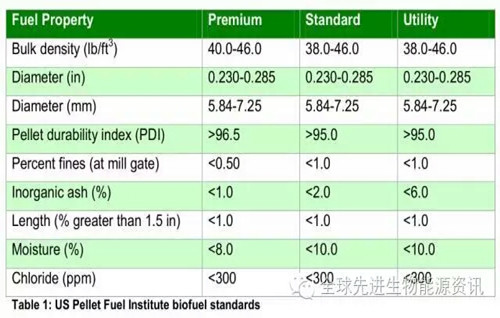

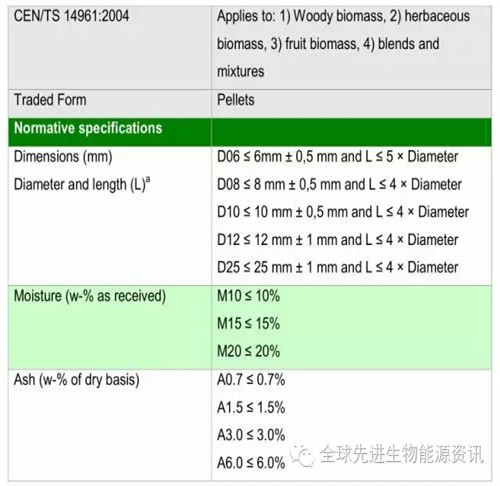

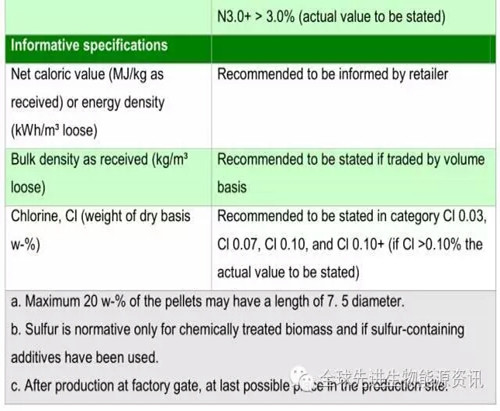

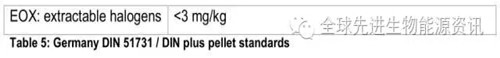

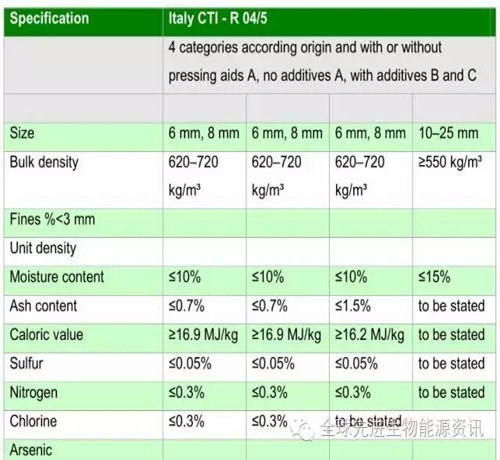

The combined standards from various European countries such as Austria, Sweden, the United Kingdom, France and Denmark are known as the European Common Standard for Solid Fuel (CEN). The European Committee for Standardization (CEN/TC 335) has prepared technical specifications and testing methods for solid biofuels. CEN/TS 14961 gives the standards for the densified solid fuels like pellets and briquettes. Below lists the individual standards for solid fuels followed by different countries such as Austria, Sweden, the United Kingdom, France, and Denmark, although these individual standards have been replaced with a common standard called the European Common Standard for Solid Fuel (CEN).

Common European solid biofuels standards were established to avoid ambiguity; previously, many European countries had their own standards. The European Committee for Standardization (CEN/TC 335) prepared technical specifications and testing methods for solid biofuels. The following are some of the standards developed for classifying properties of solid biofuels based on CEN:

Classification of biomass based on origin. Based on CEN/TS 14961, the biomass is classified based on its origin and divided into these subcategories:woody, herbaceous, fruit, and blends and mixtures.

Major traded forms of solid biofuels.

Technical specifications for pellets and briquettes according to CEN

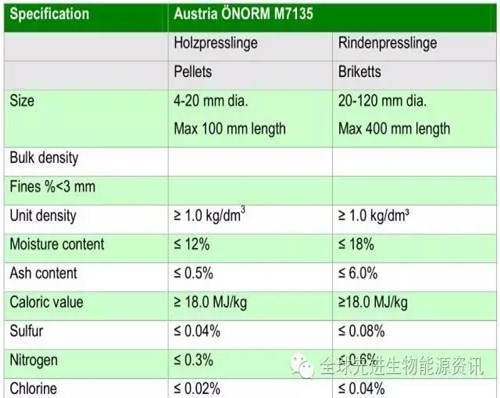

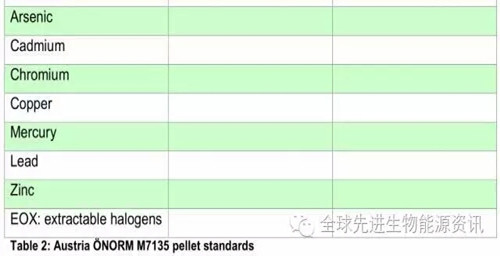

Austria

The Austrian Federal Ministry for the Environment devised a special environment label for biomass fuels. Only raw material from natural wood is allowed (sawdust, shavings, etc.). Use of materials such as packaging, coatings, glues, chipboard, or fiberboard residues is forbidden. Chemical parameters, testing methods, and limit values are similar to those in ÖNORM 7135.

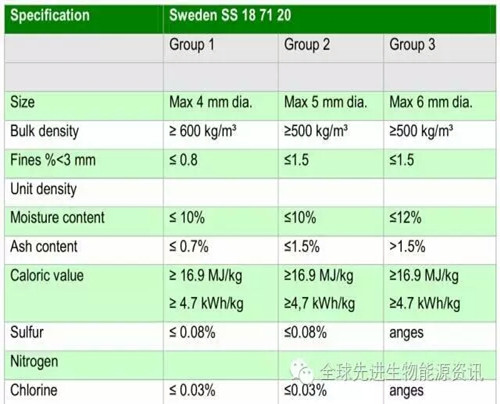

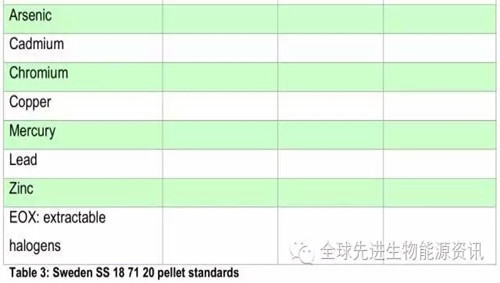

Sweden

Pellsam, the Swedish wood pellet trade body, was set up by manufacturers and suppliers of pellet heating equipment to establish standards for wood pellets for heating purposes.

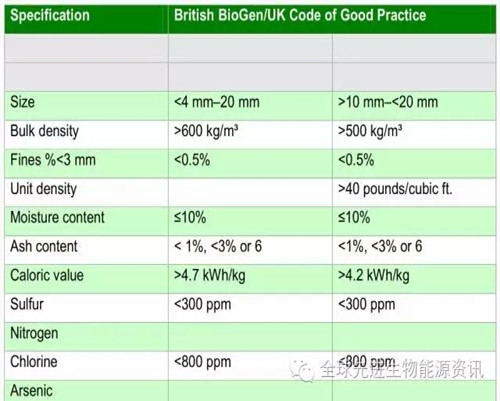

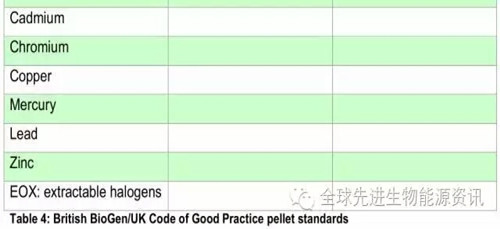

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom (UK) pellet market started with a project to introduce wood pellets to the UK with the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI). In the frameworkof this project, British BioGen have produced codes of good practice for biofuel pellets and pellet-burning room heaters <15 kW. The codes of good practice were developed as an interim measure and will be superseded by the European Standards for Solid Biofuels once they are published.

France

The French-based International Association for Bioenergy Professionals, ITEBE, created a Pellet Club. Its aim is to promote the quality of fuels and it has established a quality label. The ITEBE quality charter for pellet manufacturers (BIG, French Pellet Club, Charte Qualité) does more than simply outline the various wood pellet standards that exist in Europe; it offers specific advice on determining a quality pellet for various uses.

Denmark

In Denmark the general environment labels, such as Svanenmärket (the Scandinavian Blue Angel) or Die Blumme, are used for pellets.

Online Mall

Online Mall